Music is the universal language

“Glory to God in the highest heaven, and on earth peace to those on whom his favor rests.” - Luke 2:14

Premier Guitar

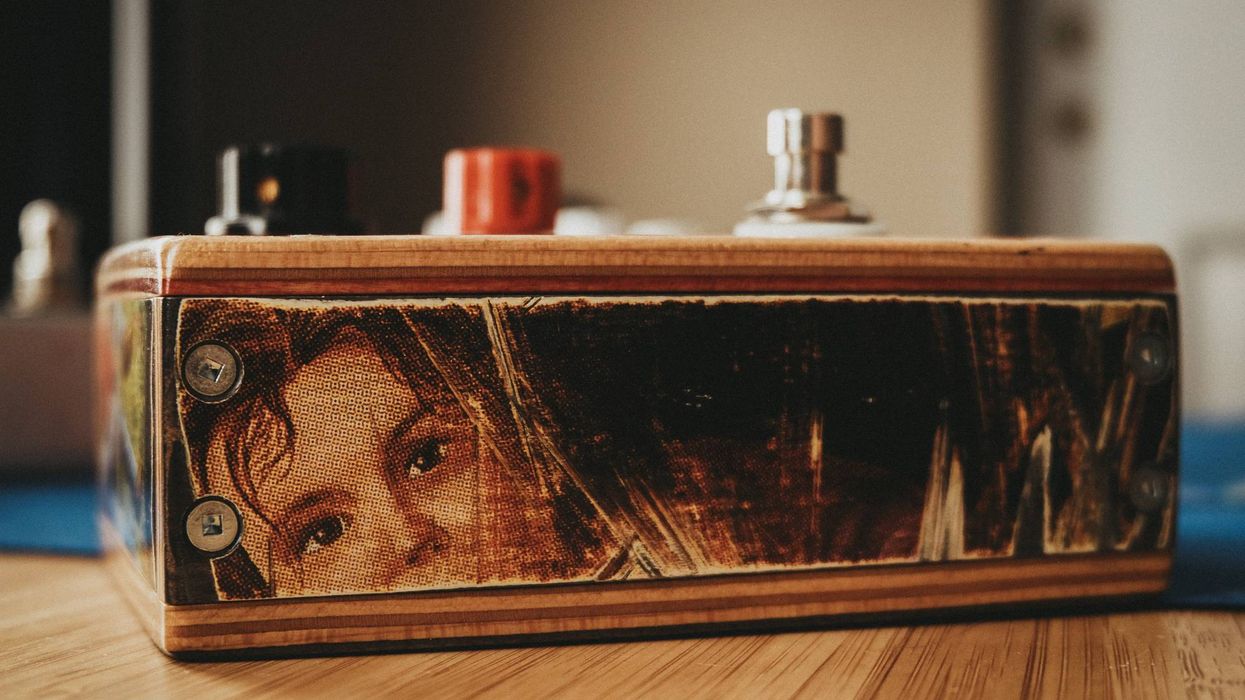

Nuclear Audio Introduces Fission Drive

Boutique effects company Nuclear Audio has introduced their debut pedal: the Fission Drive is two drives in one pedal, each acting on different parts of your guitar or bass signal.

With the Fission Drive you can split your signal into highs and lows at a frequency you select, then drive them each separately – from subtle breakup to thick distortion. Apply separate outboard effects to each channel using the independent effects loops. Use the recombined signal from the output jack or just use the send jacks from the effects loops to drive separate rigs – or use all three.

Nuclear Audio’s unique approach to clipping, not based on any previous circuits, smoothly and dynamically transitions between clean, soft clipping, and hard clipping, providing unparalleled responsiveness and dynamics while maintaining exceptional clarity.

Fission Drive highlights include:

- Separate drives for highs and lows, each with their own gain and level controls

- High/Low gain switch on each drive channel

- Control the frequency where the high and low channels are divided

- Post-drive effects loop send/return jacks for each channel

- Notch switch enables an aggressive scoop at the selected split frequency

- True bypass on/off stomp switch

The Nuclear Audio Fission Drive is available now for $300 street price from www.nuclear-audio.com and select retailers.

Set the World Afire: Dave Mustaine on Megadeth's Final Album and a Lifetime of Riffs

Dave Mustaine didn’t think he’d make it this far. Not the 40 years, not the 17 albums, certainly not the moment he’d be sitting down to talk about Megadeth’s final studio record. But here we are, more than four decades removed from that first gig at Ruthie’s Inn in Berkeley, California (February 17, 1984, to be exact), where the ceiling was so low “you could touch it from the stage,” and Mustaine was still figuring out if he even wanted to be a singer.

Could he have imagined that, in 2025, Megadeth would still be his band? “I didn’t think I was gonna live this long, honestly,” Mustaine admits during a video call, his voice still recovering from a bout of bronchitis that plagued him throughout a recent tour of Europe and the U.K. with Disturbed. Now 64, he’s dealing with health challenges that would have sidelined most musicians years ago—throat cancer, a “fused” neck, radial nerve damage in his arm. But he’s still here, still playing, still shredding. And that first Megadeth show is etched in his memory with remarkable clarity. “The history of that band was, we liked to party,” he recalls. “Ruthie’s was also a jazz club, so we had that temptation running through the band.” They played with drummer Lee Rausch—“I don’t know what happened to Lee, he was a good kid”—that night, and the lineup was still in flux. On guitar alongside Mustaine was Kerry King, on loan from Slayer, and Mustaine hadn’t even fully committed to singing yet. That decision didn’t come until bassist Dave Ellefson asked him why he wasn’t handling vocals. “I said, ‘Because I don’t want to—and that should be good enough for you,’” Mustaine recalls with a laugh. “But I also didn’t wanna hurt the guy’s feelings, ’cause Dave was younger and looked up to me. So I said, ‘Okay, I’ll try it.’ In a weird way, I have David Ellefson to thank for my singing career.”

Fast forward through the decades—through 1986’s Peace Sells... But Who’s Buying?, through 1990’s Rust In Peace, through 12 Grammy nominations and one win, through lineup changes and personal demons conquered—and Mustaine finds himself at an unexpected crossroads. The band’s latest album, simply titled Megadeth, will mark their 17th and final studio effort.

The decision wasn’t made lightly, and it wasn’t made in a single moment. “I would still keep going if I was not battling these things,” Mustaine explains, referring to his ongoing health struggles. “But I just don’t want to go out onstage when I’m not my best. There were many nights on the Disturbed tour where I was in full-blown bronchitis, hopped up on antibiotics and steroids to get rid of the inflammation. That doesn’t feel good. I’m not a guy that likes being sick.”

“I didn’t think I was gonna live this long, honestly.”

The recording process itself proved physically grueling. Working with producer Chris Rakestraw at various points throughout 2024, Mustaine and his current lineup—virtuosic Finnish guitarist Teemu Mäntysaari, Belgian drummer Dirk Verbeuren, and bassist James LoMenzo—did sessions in marathon stretches. “We did about four weeks straight, 12-hour days,” Mustaine recalls. “And I told my management, ‘I don’t know how much longer I can do this.’ My hands were throbbing and my back was hurting from sitting up for that long. What I remember during some of those sessions was torture, when they make people sit for long periods of time.”

Yet despite the physical toll—and the weightiness of knowing this would be Megadeth’s final statement—there was an openness and fluidity to the sessions. The songs were numbered rather than titled during recording—“Tipping Point,” the album’s explosive opener, was “song number nine”—because Mustaine changed titles so many times. “Going into the studio, I don’t really ever have a plan,” he says. “I have songs and we go in to record them, but I think open-mindedness going into the studio has been really good for us. A lot of times you’ll be working on a song and you’ll get an idea, and then you’ll have a completely different song come out of it.”

STUDIO GEAR

Guitars

- Gibson Dave Mustaine Flying V EXP

- Gibson Flying V with Evertune bridge

Amps

- Marshall JVM410HJS Joe Satriani Edition

- Marshall 1960DM Dave Mustaine 4x12 cabinet

- Mesa Boogie 4x12 cabinet

- Neve Brent Averill 1272 preamp (no EQ, no FX)

Effects

- TWA Chemical Z overdrive

- MXR Phase 90

- MXR Flanger

- Fortin ZUUL+ noise gate

- Source Audio EQ2

- Peterson StroboStomp HD tuner

- Peterson StroboRack tuner

- Korg DTR-1 rackmount tuner

Picks & Strings

- Dunlop medium picks

- Gibson Dave Mustaine strings, signature gauge (.010-.052)

That openness extended to his bandmates. “Dirk wrote music. James wrote music. Teemu wrote music,” Mustaine notes. “Even our producer chimed in a couple times. Good producers are supposed to do that.” The democratic approach reflects both his confidence in his current lineup and his recognition that fresh perspectives keep the music vital. “I believe with James and Dirk and Teemu’s ideas, this record had a lot of really fresh ideas. Obviously I have my fingerprints on it, but we’re a band.”

The album’s 11 tracks find Megadeth operating with deadly precision—economical, direct, savage. “Tipping Point” kicks off with a blistering guitar solo that gives way to Mustaine’s unmistakable snarl. “I Don’t Care” channels punk fury into defiant aggression. “Let There Be Shred” celebrates guitar virtuosity with mythic, apocalyptic imagery about thrash metal’s birth—a “Mount Olympus kind of thing,” as Mustaine puts it—while cuts like “I Am War” and “Made to Kill” deliver the technical thrash assault the band has honed across four decades.

For Mustaine, the division of labor between himself and Mäntysaari came down to serving the song. “If the rhythm’s really difficult, I’ll usually play the rhythm and let my guitarist do the solo,” he explains. “And if the rhythm’s really easy, I’ll let them do the rhythm and me solo. A lot of that is because these guys are all virtuosos and I’m self-taught, so there’s a limit to what I know how to do. A lot of what my soloing is, is just statements. We could be listening to a really beautiful solo, and then I’m gonna come and stomp through your gardens with combat boots.”

He points to the solo in “Let There Be Shred” as an example. “It’s kind of a hippie solo,” he says. “Teemu’s shredding, and then you go into this kind of slow-motion riff in the middle of the song. And I felt that having a burning solo over that part would be wrong because the rhythm was a really cool rhythm. A lot of times when people play solos, they think the solo’s more important than the song.”

It’s a philosophy Mustaine has carried throughout his career, one rooted in his identity as what he calls “a guitarist that sings” rather than a rhythm player or lead guitarist. “The term ‘rhythm guitar player’ seems a little diminishing for me,” he says. “I love the riff.”

And how committed is he to that principle? When asked what he sees as Megadeth’s main contribution to metal over the decades, he doesn’t hesitate: “Riffs.” It’s the riff—more than the solos, more than the hooks, more than even his distinctive snarl of a voice—that defines the band’s legacy in his mind.

“Sometimes you just want to hear something that makes you wanna kick trash cans over.”

That riff-centric approach announced itself the very first time Mustaine plugged in with his pre-Megadeth band, Metallica. “When I went to Norwalk [California] the day that I met James Hetfield and [original Metallica bassist] Ron McGovney, I didn’t know what was gonna happen,” he reflects. “Nobody did. But I had my style, and it was based around the riff.”

That style made an immediate impression. “I went in there and I didn’t have any Marshalls yet because I was just starting to get serious. I had these Risson amps—they were tan, so from the moment I set up my stack, I was different. I plugged in my guitar and I started warming up, and I kept warming up and warming up. And I finally said, ‘Where the fuck are these guys?’ I set my guitar down and switched my amp to standby. And then I went out there and I said, ‘Man, where’s my audition?’ They said, ‘You got the gig.’ So I got my job just by warming up.”

That period of time proved to be the crucible when thrash metal’s DNA was forged. When Hetfield picked up a guitar at a subsequent rehearsal—they’d been working with a second guitarist who showed up to a gig at the Whisky a Go Go, “in Def-Leppard-circa-’86 clothes, with a giant feather in his ear”—Mustaine was floored. “It blew my mind because he was so good. I kind of thought, where were you when we were auditioning a second guitar player? He was as good as he is today. James is a masterful guitarist.”

The fact that two musicians who would essentially define thrash guitar—the palm-muted down-picking fury, the intricate riffing, the speed and precision—were sitting in the same room together as teenagers remains remarkable. “I hear influences on everything,” Mustaine says. “I’ll be listening to a TV show and somebody will be playing the soundtrack, and it’s either copying a lick from me or from Metallica. I just take it all in stride. I feel very honored to have been able to make a name for myself.”

That history—and Mustaine’s complex, decades-long relationship with Metallica following his dismissal in April 1983—informs one of Megadeth’s most surprising inclusions: a version of Metallica’s “Ride the Lightning,” which Mustaine co-wrote with Hetfield, Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich, and late Metallica bassist Cliff Burton.

“As I come full circle on the career of a lifetime, the decision to include ‘Ride the Lightning,’ a song I co-wrote with James, Lars, and Cliff, was to pay my respects to where my career first started,” Mustaine explains. “It showcases the spider riffing and the grunting fretting—you fret a G flat power chord and you slide up into the G—technique that I brought [to the band]. I thought it was just a great way to pay my respects to James and Lars and to close the circle.”

Does he consider his take on “Lightning” a cover version? “No, because I wrote the song too. I think other people will say that, but if you’re asking me, I don’t think it’s a cover song. When we played it for people who are fans of that band and that song, the consensus has been that we did a fitting homage. I think we did it at least as good.” He pauses. “It’s a little faster.”

The album closes with “The Last Note,” perhaps Mustaine’s most introspective song—a reflection on career’s end that acknowledges both the cost and the glory. “They gave me gold, they gave me a name / But every deal was signed in blood and flames,” he sings, before delivering a final testament: “I came, I ruled, now I disappear.” Yet Mustaine insists he’s not dwelling on endings. “I’m at a place in my life right now where I’ve been reflective, but not too much,” he says. “I do have days full of satisfaction, a lot of contentment with everything that’s going on.”

As for the tools that helped forge this final statement, Mustaine has come full circle. After years playing various Flying Vs, he’s now a Gibson ambassador, wielding a signature model that he describes with genuine reverence. The collaboration, he says, enabled him to dial in exactly what he desired—the right pickup configuration, the electrical schematic for his knob placement, a neck that’s very different from the standard Gibson Flying V. “Flying Vs are the most popular guitar in music,” he notes. “When people think of rock bands, they always draw one guy with a Flying V. I grew up loving the V, and to be [Gibson’s] number-one guy right now with it—the guitar is a monster.”

That monster will get plenty of use in the years ahead. Megadeth’s farewell tour will extend well into the future—Mustaine estimates three to five years of dates to properly close out Megadeth’s legacy, including runs supporting Iron Maiden and headlining with Anthrax and Exodus in support. “[Exodus guitarist] Gary Holt and I are like this,” Mustaine says, holding up crossed fingers. “Blood. He’s actually my oldest friend in the music business besides the guys in Metallica.”

“The term ‘rhythm guitar player’ seems a little diminishing for me. I love the riff.”

But he’s already gaming out how to handle that final show. “I was joking around and I said to my management, you should book the tour and then have a couple fake shows listed at the end. So I’ll do the last show thinking there’s still a few more to go, and then you’ll tell me that was it. And I’ll punch you in the face instead of breaking down and sobbing on stage.”

End it in anger instead of sadness? “Yeah,” he says with a laugh. “It’s more ‘Dave.’”

It’s quintessential Mustaine, wrapping emotion in, to use his words, a combat boot. From that first show at Ruthie’s Inn (where Mustaine wielded a pretty killer natural-finish BC Rich Bich that was later stolen) through countless tours and lineup changes, through personal and professional battles, he’s persevered. Does he wonder if younger musicians understand his place in metal history, the role he played in shaping thrash? “I don’t really know how much modern musicians know,” he admits. “If they’re influenced by a band that was influenced by a band that was influenced by me or Metallica, do they know the story? But I’m okay with myself, so I don’t feel the necessity to have people sing my praises. I’m really comfortable with who I am.” He laughs. “A freckle-faced redhead. You don’t think I was picked on growing up?”

For now, though, Mustaine is very much still here, and still vital. The hands may throb and the voice may rasp, but the fire that drove a red-haired kid to pick up a guitar and create a sound no one had heard before still burns. Megadeth delivers on that fire. “Sometimes you just want to hear something that makes you wanna fuck or fight, you know?” he says with a laugh. “Something that just makes you wanna kick trash cans over.”

As for that final show, whenever it arrives, Mustaine will walk offstage knowing he gave everything he had. And whether or not his management actually pulls off those fake extra gigs he joked about, there likely won’t be anger or tears—just gratitude for what was. “I’m really blessed,” he says. “And I’ve loved every moment of this.”

State of the Stomp: In Defense of the Mono Pedal

If you scroll through the comments section of most pedal demo videos, you’ll see a familiar refrain: “Why not stereo?” And while stereo has its merits, I’m here to defend the mono signal chain. Before treating stereo as an automatic upgrade, it’s worth taking a closer look at when it helps, when it hinders, and why mono might actually be the more powerful choice for most players.

Stereo is often seen as a bonus for a pedal, a feature that a player may use in the rare case they have a stereo signal. But I’d argue that it can sometimes hurt the pedal’s design. Even with digital pedals, stereo requires extra circuitry to account for both signal paths. This means the pedal will certainly be more expensive. It also means the pedal will likely be bigger, to house both the added circuitry and the additional jacks to support the stereo in and out. So if you’re playing in mono most of the time, don’t worry about that stereo option.

For those who actually use a stereo pedalboard, there’s still plenty to consider. I’ve noticed that the majority of stereo players tend to use it in recording scenarios, but this is also where I find stereo to be the most harmful. Say you’re cutting a track with single takes of each part recorded through stereo effects—while each individual track is wider than a mono recording, together they add up to create a flattened mix because each track is occupying the same area in the stereo field. While it may sound backwards, a mix with multitracked guitars recorded in mono allows for a wider sound. Each track being slightly different creates a perceived physical space, much like a choir sounds fuller and richer than an individual voice.

Furthermore, let’s be honest: Most people don’t listen to music in stereo, either. Have you ever been to a friend’s house where their “stereo” setup consisted of two speakers placed across the room at different heights? And certainly even those who care about stereo have listened to music through a mono Bluetooth speaker or a single headphone.

“While it may sound backwards, a mix with multitracked guitars recorded in mono allows for a wider sound.”

Mono is a great option for guitar signal chains because the guitar is ultimately a mono instrument, a sound created from a single source. By not changing the nature of the guitar, you end up getting more out of it. Embracing mono ultimately empowers every part of your signal chain—guitar, pickups, pedalboard, amp—to be used to its full potential, because you’re not trying to fit it into the needs of stereo. There’s a reason why a two-guitar band sounds so good, or why multitracking works so well. Each part can sit in its own space, live or in a mix, complementing the other to create a greater whole.

There is one use for stereo that I will admit I am very fond of. Wet/dry rigs are a great way to break out of the standard signal chain without losing some of the power of mono. This type of setup has two separate signal chains, one containing the dry signal, including simple effects like compression and distortion, and one containing the more prominent effects like delay and reverb; each runs into a separate amp to be played side by side. In fact, while wet/dry is often thought of as a type of stereo rig, I would argue that it is a version of leveled-up mono—dual mono. Here you can have all of the benefits of two signal chains without the worries of keeping that perfect stereo even-ness, and the two work together to create something larger that is defined by the differences between each signal.

To sum up, stereo isn’t inherently bad—it’s just not the universal upgrade it’s often assumed to be. For many players, chasing stereo introduces more compromises than benefits. By embracing the guitar’s mono nature, you can make more intentional choices about your rig and the playing experience itself. And by understanding these distinctions, you’ll be better equipped to choose the right tools and get the most out of the instrument you already love.

Boss XS-1 Poly Shifter Review

Any effect can color a guitar’s personality and language. But Boss’ new XS-1 Poly Shifter literally stretches the instrument’s vocal range. With the ability to shift input by +/-3 octaves or semitones, it can turn your guitar into a bass, a synth, or a baritone, or function as a capo. It also seamlessly generates harmonies for single note leads and keeps up with quick picking without any apparent latency. Furthermore, the pedal is capable of stranger fare that stokes many out-of-the-box ideas. But if you’re a guitarist that plays more than one role in your band—or musical life in general—the XS-1 can be a utilitarian multitool, too. It’s a pedal that can live many lives.

- YouTube

The XS-1, which was released alongside its bigger, more intricate sibling, the XS-100, is an accessible route to exploring pitch shifting’s potential. Housed in a standard Boss enclosure, it doesn’t consume a lot of floor space like the XS-100 or DigiTech’s Whammy. And while it achieves this spatial economy in part by forgoing a built-in expression pedal (which could be a deal breaker for some potential customers) it’s still capable of +/- seven semitones and a +/- three-octave range that can be utilized in momentary or latching applications.

Slipping, Sliding, and Twitching

Though digital pitch shifters have always been capable of amazing things, early ones sounded very inorganic at times. High-octave sounds in particular could come across as artificial, like the yip of a robot chihuahua plagued by metal fleas. Some very creative players use these colors—as well as the most sonorous pitch shift tones—to great effect (Nels Cline and Johnny Greenwood’s alien tonalities come to mind). In other settings, though, these older pitch devices can be downright cringey.

“The pedal clearly represents several leaps forward from first-generation pitch shifters.”

The XS-1 belies digitalness in some octave-up situations. But the pedal clearly represents several leaps forward from first-generation pitch shifters. Tracking is excellent and shines in string bending situations. Semitone shifts can provide focused harmony or provocative dissonance depending on the wet/dry mix and which semitones clash or sing against the dry signal. At many settings the XS-1 feels alive and organic, too, with legato lines taking on many of the touch characteristics of a violin-family instrument. You get far less of a note-to-note “hiccup,” and glissandos take on a beautifully fluid feel—with or without a slide—letting the XS-1 deliver convincing pedal- and lap-steel-style textures when you add a single octave up. (Such applications sound especially convincing when you kick back on guitar tone and restrict your fretwork to the 3rd through 5th strings, which keeps digital artifacts at bay.)

Mixmaster Required

The most crucial XS-1 control is the mix. For the most convincing bass, baritone, and 12-string tones, you’ll want a fully wet signal. But composite sounds can be awesome, too. You can use the control’s excellent sensitivity and range to highlight or fine tune the prominence of a consonant harmony. But it’s sensitive enough to make blends with dissonant harmonies sound a lot more intentional and integrated. And many of these eerie, wonky, off-balance textures are extra effective when introduced in quick bursts via the momentary switch. (That switch can also deliver great flashes of drama with more consonant harmonies—like dropping in a 3rd or 5th above a resolving chord in a verse.)

You can get creative in other ways using dissonant blends. Droney open tunings can yield fields of overtones that sound extra fascinating with delay, reverb, or 12-string guitar… or all of them! Dialing in blends that really work takes some trial and error, and you’ll definitely hit a few awkward moments if you’re navigating by instinct alone. But those same experiments often uncover real gems—especially in the pitch-down modes, which tend to produce more mysteriously atmospheric textures than their pitch-up counterparts.

The Verdict

Boss’ most straightforward pitch shifter covers a lot of ground. If you play in a duo, trio, or small band, it can expand that collective’s stylistic and harmonic range. It’s small, at least relative to treadle-equipped pitch shifters, so if you’re not a pitch shift power user, you don’t sacrifice a lot of room for an effect you might only employ occasionally, and you can still use the expression pedal jack to hook up a pedal for dynamic pitch control. The $199 price puts it in line with competitors of similar size and feature sets, but the XS-1 is a great value compared to more elaborate, treadle-equipped pitch shifters. If you’re taking your first forays into pitch shifting, or know that you need only the most straightforward functions here, it will ably return the investment. And along the way, it might even unlock a whole cache of unexpected tonal discoveries.

Recording Dojo: How Samplers and Loopers Create Beautiful Chaos

Most people think of samplers as drum machines with delusions of grandeur—four-bar loops, predictable patterns, and neatly sliced bits living forever in the prison of the grid. But for me, samplers and loopers are something completely different. They’re instruments of disruption. They’re creative accelerants. They’re circuit breakers designed to shock me out of my comfort zone and force my compositions, productions, and performances into strange, exhilarating new shapes.

One of my favorite studio practices—and something I encourage my Recording Dojo readers to experiment with—is to sample your performances. Not a preset library, not a pack from somebody else, but use your own melodic lines, motifs, rhythms, textures, and half-formed ideas. There’s something magical about hearing your own musical DNA come back to you in an unfamiliar, mutated form. It’s like collaborating with a version of yourself from an alternate timeline.

The real thrill isn’t about capturing pristine performances. In fact, it’s often the opposite: I’ll grab a phrase that’s imperfect, or mid-gesture, or harmonically unresolved, and drop it into a sampler purely to see what it becomes. When you do this, your musical habits—your well-worn licks, default rhythms, and predictable choices—don’t stand a chance. The sampler shreds them, recontextualizes them, and hands them back as raw material for re-writing, re-arranging, or composing something that never would have emerged in a linear workflow.

Sometimes the transformation is subtle—a lick becomes a rhythmic ostinato, a sustain becomes a pad, a passing tone becomes a focal point. Other times the sampler just mangles it, spits it out sideways, and you think, ‘Oh… now that’s interesting.’ Either way, it becomes a tool for breaking patterns, both musically and psychologically.

My Process: Mutations, Not Replications

My approach to sampling isn’t any more complicated than anyone else’s. I’m not using some secret, elite technique. I’m simply collecting fragments—little melodic cells, rhythmic quirks, harmonic gestures—and giving them permission to misbehave.

I’ll chop up key licks into uneven slices, or isolate just the back half of a phrase, or extract a rhythmic hiccup that wouldn’t survive in a normal editing session. Then I reassemble these bits with the expectation that they won’t behave. I want mutations. I want the musical equivalent of genetic drift. I’m not trying to color within the lines; I’m trying to see what happens when I throw the coloring book across the room.

Once the sampler gives me something intriguing, I run these new creatures through chains of further processing: glitch delays that stutter and fold the sound into origami-like shapes, micro-loopers feeding into overdrives or fuzz pedals, shimmering reverbs that stretch a 200-millisecond blip into a widescreen texture. The result can be anything from a ghostly sustained pad to a snarling, percussive accent, to a completely alien harmonic bed.

You can use these elements as alternate melodic lines, counterpoint, ambient beds, transitions, ear candy, or even structural material for entire songs. And because the source is you, the end result stays connected to your musical identity—just bent, twisted, and refracted into something fresh.

Outcome Independence: The Spirit Behind the Process

If there’s one thing that makes this approach powerful, it’s letting go of the expectation that what you sample must “work.” This is pure experimentation, not product-driven crafting.

I’m outcome-independent when I do this. I’m not looking for a result so much as engaging in the joy of the unknown. Some days nothing meaningful emerges. Other days I strike gold. But either way, the process sharpens my creative instincts. It keeps me curious.

“There's something magical about hearing your own musical DNA come back to you in an unfamiliar, mutated form.”

I use this same strategy when producing artists or working on film and soundtrack material. Recently, I applied it to pedal steel—an instrument known for its lyrical beauty—and the resulting textures were … well, not beautiful in the traditional sense. They were fractured, shadowy, almost Jekyll-and-Hyde. Perfect for a track built around the duality of personality. The clients absolutely loved the unpredictable, emotive soundscape those mutated pedal steel lines created.

Some Favorite Tools for Sonic Mutation

You don’t need a million pieces of gear to do this. A single sampler and a single effects chain can take you far. But here are a few of my favorite “chaos engines,” all of which I own and use regularly:

• Teenage Engineering OP-1 Field – A sampler, synth, tape machine, and chaos generator disguised as a minimalist art object. Its sampling engine and tape modes are perfect for tonal mutations.

• Teenage Engineering EP-133 K.O. II – A quick, dirty, wonderfully immediate sampler for slicing, punching, and recombining your ideas without overthinking.

• Omnisphere 3 – The granular engine alone is a goldmine for turning simple samples into cinematic, evolving textures.

• NI Maschine – Still one of the fastest environments for grabbing a sound, flipping it, and building an idea around the unexpected.

• …and whatever else you have lying around. The point is exploration, not allegiance to any one workflow.

Final Thoughts

Sampling your own voice as an instrumentalist—and then breaking it—reminds you that creativity doesn’t live in the safe, predictable spaces. It lives in the moments where you lose control just enough to discover something new. Give your sampler permission to surprise you, confuse you, and sometimes even challenge your sense of what you sound like. That’s where the good stuff begins.

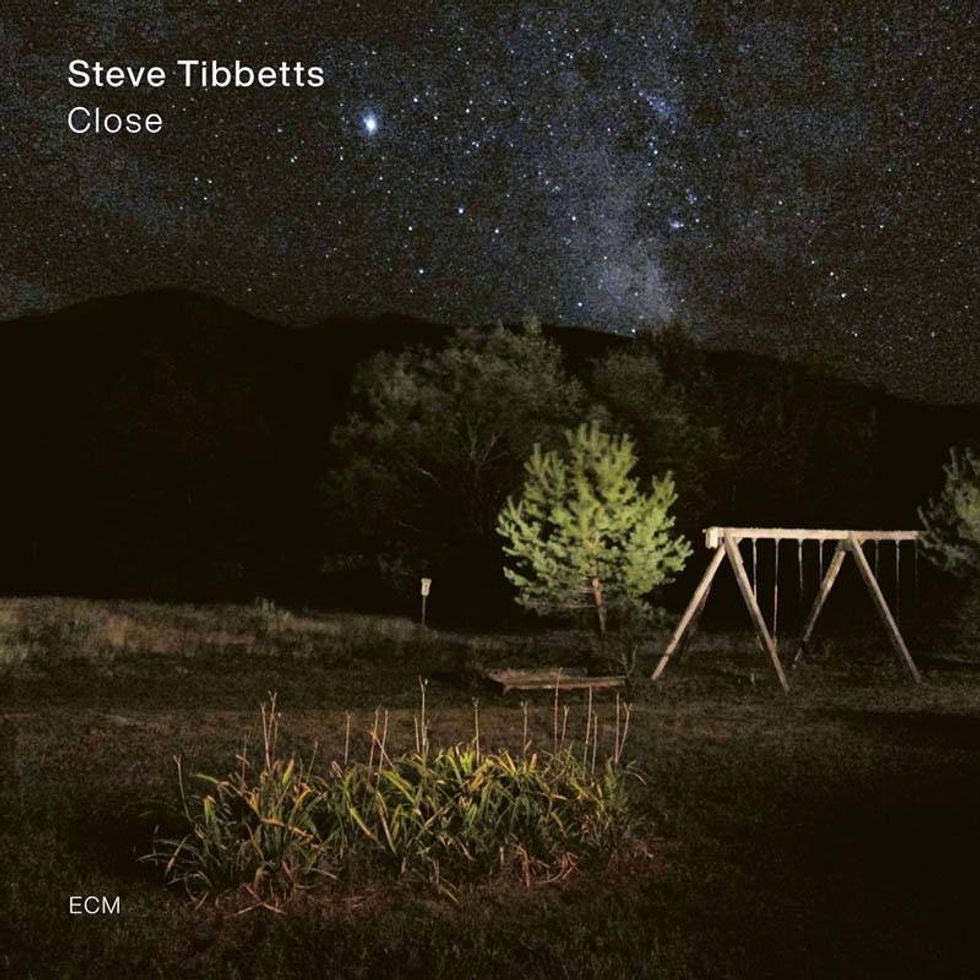

Listening and Looking with Steve Tibbetts

There is a specific thread of experimental musician whose real motive is to deal in mystery and wonder. Think conceptualists like Brian Eno and David Bowie, sonic conjurers Sunn O))), transcendent improvisers as varied as Alice Coltrane and Loren Connors, song mystic Annette Peacock—each artist’s work is tied to something that happens beyond the notes, something bigger than just the sounds we hear. And for the listener, there are no easy answers. You can research and dissect compositional and production methods, know all of the gear that was used inside and out, break down all of the influences. But you’re always left with something to chase, to try and understand more deeply. For some, that’s the thrill.

Steve Tibbetts works with these ineffable parts of music, and he has ever since his 1977 self-titled debut. His albums create experiences that, at times, approach definability, but remain elusive: He’s a guitarist, but his music isn’t necessarily “guitar music”; his work is rooted in traditions, but it’s not traditional. So, what is it?

Since the beginning of the 1980s, Tibbetts’ records have been released primarily on the ECM label—the longstanding preeminent home of meditative and ambient jazz and jazz-adjacent sounds. On his earlier releases, you may hear grooves assembled around percussion from various global cultures mixed with suspended 12-string acoustic strumming, soaring evocative melodies, and, at times, blazing electric guitar solos. The cover images on his albums are striking, and often created by the composer himself, capturing some moment in a similarly un-pinnable land—check out the rock formations on either 1980’s Yr or 1986’s Exploded View, for example. The whole blissed-out package is conceptually inspired by place and tradition, yet totally untethered and fresh.

“If I just sat around and played guitar all day long, I don’t know how that would go.”

On more recent releases, and especially on his latest, Close, Tibbetts’ sound has evolved toward something else—more big-picture, but also more personal. Raw and organic sounds mix with a futuristic sonic landscape (and yet, he uses antiquated technology to create those sounds). Close feels like a universal meditation, a grand vision that pulls sounds from across the globe and reaches beyond, toward some distant sonic horizon, overcoming instrument and process. Basically, it sounds like nothing else.

Enigmatic as that is, over the course of an hour or so on our video call, Tibbetts himself proved to be anything but. Speaking from his wood-paneled Minnesota studio, where he’s made much of his music since 1985, he revealed his process and the philosophy behind it—a methodology deeply tied to his own experience of the world.

For Tibbetts, creation starts simply. “You have to sit down and put your hands on the instrument,” he explains. And it’s all about vibe. “Sometimes, it's a matter of getting the guitar warmed up. Hoping for the right humidity in the room.”

In order to keep things moving, his studio is always ready to go—his mics in position and DAW loaded up. “The process is to come to the studio, make a cup of coffee, begin to play, and see if we get to that point,” he says. He starts solo, bringing in other players further down the line. “Nobody cares how loud I get here. I’ve got a couple of Marshall JCM 800s, a younger Marshall, and as long as I wear adequate ear protection, I’m fine. I can get the sound that I need.”

Steve Tibbetts’ Gear

Guitars

Martin D-35 12-string

Martin DM-12

(Fishman TriplePlay pickup for acoustics)

1971 Fender Stratocaster

Amps

Marshall JCM 800 combo

Matchless Lightning 15 watt

Strings

John Pearse custom 12-string sets with double courses instead of octaves

GHS Boomers (Medium)

The days slowly add up. “Do you know what it’s like when you wake up in the night and your fingers are throbbing?” he asks. For him, “that usually means it’s been a good, productive day at the studio. Then you come back the next day. Is there anything worthwhile? Probably not. But after five or six years, you’ve got something—30 minutes, 40 minutes worth of pieces.”

As the music takes form, at some point, he brings in collaborators. On Close, Tibbetts is accompanied by percussionist Marc Anderson, his longest-running musical partner, and drummer JT Bates.

“It begins to sort of assemble itself,” he continues. “It is a little bit of a cliché, but at a certain point, you are in service to the music that you've created and you just need to do a good job with it.”

He quickly balances that thought with a dose of reality: “Mostly, the process is one of tedium, boredom, failure, and actually figuring out what I need to do when I've started the car and am on the way home.”

“What a good thing to do, to listen and look at stuff.”

Tibbetts’ music isn’t purely an in-the-studio creation, though. The world outside his walls plays a major role. “If I just sat around and played guitar all day long, I don’t know how that would go. Maybe there are some guitar players who can do it,” he muses. “Sometimes, the process is to give up entirely and go someplace a long ways away and listen to some loops or little lines that you have as you’re walking around.”

That’s the specific method Tibbetts followed on 2018’s Life Of. He explains: “There’s an area in northern Nepal, close to Tibet, called Lhasa. Difficult to get to, but a friend of mine, a professional clown, named Marian, said, ‘We’re going to Lhasa, do you want to come?’ And I thought, I’ll go there, and I’ll make little mp3s, 60 minutes or so, to listen to while we're walking. That’s what I did. When I came back, I had a good idea of what I wanted to do to put things together.”

For those who can’t travel quite so far, he recommends just getting out of your surroundings. “What a good thing to do,” he enthuses, “to listen and look at stuff. Even mixing. I’m looking at the same paneling here all the time. It doesn’t work. You can take your little laptop now and go to a coffee shop and say, ‘This song is gonna be about this couple over here, or that guy drinking coffee by himself.’ Just mess with your mind a little bit.”

“If it’s not fun, I’m not interested.”

Travel has inspired Tibbetts work throughout his career, thanks especially to his early experience working for study-abroad programs in Bali and Nepal. “That was hard work,” he explains, “but I got to live in cultures where there was different music. Balinese gamelan, if I hear it in Minnesota, it’s just annoying. But over there, it sounds like it fits. The double drumming technique, I had to be in it and study it to bring it back.”

Across the globe, Tibbetts has collected the recordings to incorporate in his music. The idea goes back to his 1997 album, Chö, a collaboration with Tibetan singer Choying Drolma. “We made that record in Kathmandu, Nepal,” he says. “Her singing was incredible. I didn’t want to just strum along on guitar, I wanted to use some of the sounds of Tibetan longhorns, some of my own sounds like bowed hammered dulcimer, my wife’s wine glasses….”

Tibbetts continues, “I did that. And then we got an offer to go out on the road. Desperation takes hold. How am I gonna do this? There’s gotta be a way.”

He devised a setup to trigger samples with his guitar using a Roland MIDI pickup that “had a cable that was about as thick as a stalk of corn that went to another box that would jack into a sampler, probably with a SCSI port.” Inconvenient, but, Tibbetts says, “it did work and we did take that on the road, and then I thought, this will be a good composing tool, this will be fun.” He pauses, and adds, “If it’s not fun, I’m not interested.”

More recently, Tibbetts switched to a Fishman wireless system to trigger the samples. But the samples themselves come from an old version of MOTU’s Digital Performer, which requires him to keep his computer “probably 15 operating systems behind what’s current now.” (He jokingly explains: “I’m working with antiquated technology. I’ve got buggy whips and wooden wheels here.”)

The result is otherworldly. Global sounds enmesh with Tibbetts’ strings, opening up the possibilities of his guitar—a sum-is-greater-than-the-parts experience where you might not realize what exactly is being played or where it’s coming from.

Knowing the sources, however, enriches the experience. Because though some of Tibbetts’ samples are created at home in his studio, many have a story. “I can still hear the chicken in the gong,” he says, launching into a story that goes back to his time working for a study-abroad program in Candi Dasa, Bali. He took the class to visit “a guy that did two things: made sacred knives that they use for ritual activities and had a gong shop.” He explains that gongs for gamelans are all made at the same time to coordinate the orchestra’s tuning, and they visited on a day where new bronze would be poured. “This was a once-in-a-lifetime thing. We went down there and spent a day watching these guys beat the shit out of these things to get them in their own tune, which is still a good 30 or 40 cents off what we would call in tune, but together it sounds good.

He continues: “I spent an extra day there sampling these gongs. I would hit the gong softly. I’d mute it. I would hit it hard.” The gong-maker was curious. “He said, ‘Let me listen to it.’ He listened to it on the headphones and said, ‘I’m sorry my chicken is squawking.’ I said, ‘It’s okay.’ And then the next thing I heard was no chicken squawking. He invited me for dinner. I declined.”

On Close, focused listening reveals another sonic element—the sound from Tibbetts’ acoustic guitar. Often more polished, it’s more raw this time around than on his other records—sometimes you’ll hear buzzing, fretting, and breath sounds. It gives his playing an intimacy, a warmth that stands out. It feels close.

Early in the creation process, Tibbetts wasn’t confident this was a direction he wanted to pursue. So he had Anderson listen to some takes. “People who work alone a lot tend to become a little inbred with themselves, start not understanding what direction they’re going in, or if they’re going in the right direction, or if anything is any good at all,” he muses. “Marc and I have been working together since 1979. His ears are very good. He made me understand that I already knew that this was okay. I just needed confirmation from him.”

He continues, “I am going for the feeling. I guess we’re always going for the feeling, but I just didn’t want to ditch a take because I happened to make a sound, a bad fret sound, a new string sound….”

With Closenow out in the world, don’t hold your breath to catch Tibbetts live—his performances are rare. When asked about this, it’s clear his days of getting in the van are long gone, adding that one-off gigs are also “not that great. It usually takes a few gigs on the road before you get your chops together, lighting, sound, loading in, loading out, your pedals, whatever you have….” But he says there are those occasional gigs that afford the travel, rehearsal time to get it together, and make a compelling enough offer. “If the gig is weird enough and far away enough,” he says, “we'll do it.”Courtney Cox Breaks Down Burning Witches Guitars, Tone, and Touring Gear

Burning Witches guitarist Courtney Cox joins the Axe Lords to talk technique, tone, and the realities of life as a modern touring guitarist. She breaks down how the band writes and records across borders, works under brutally short studio timelines, and balances locked-in rhythm playing with expressive lead work. Cox also explains why learning by ear—not regimented practice—has always driven her playing, and how ADHD shapes both her focus and creativity.

The conversation traces her path from early touring as a teenage prodigy through her years with Iron Maidens, to designing multiple signature guitars built for extended range, lower tunings, and long tours. Along the way, she gets specific about gear and discusses the realities of being a working guitarist, from social media burnout and Patreon economics to perfectionism onstage—and knowing when to stop forcing it and just play.

Follow Courtney @ccshred

Axe Lords is presented in partnership with Premier Guitar. Hosted by Dave Hill, Cindy Hulej and Tom Beaujour. Produced by Studio Kairos. Executive Producer is Kirsten Cluthe. Edited by Justin Thomas (Revoice Media). Engineered by Patrick Samaha. Recorded at Kensaltown East. Artwork by Mark Dowd. Theme music by Valley Lodge.

Follow @axelordspod for updates, news, and cool stuff.

The Lowdown: Why Do We Never Take Lessons as Professional Musicians?

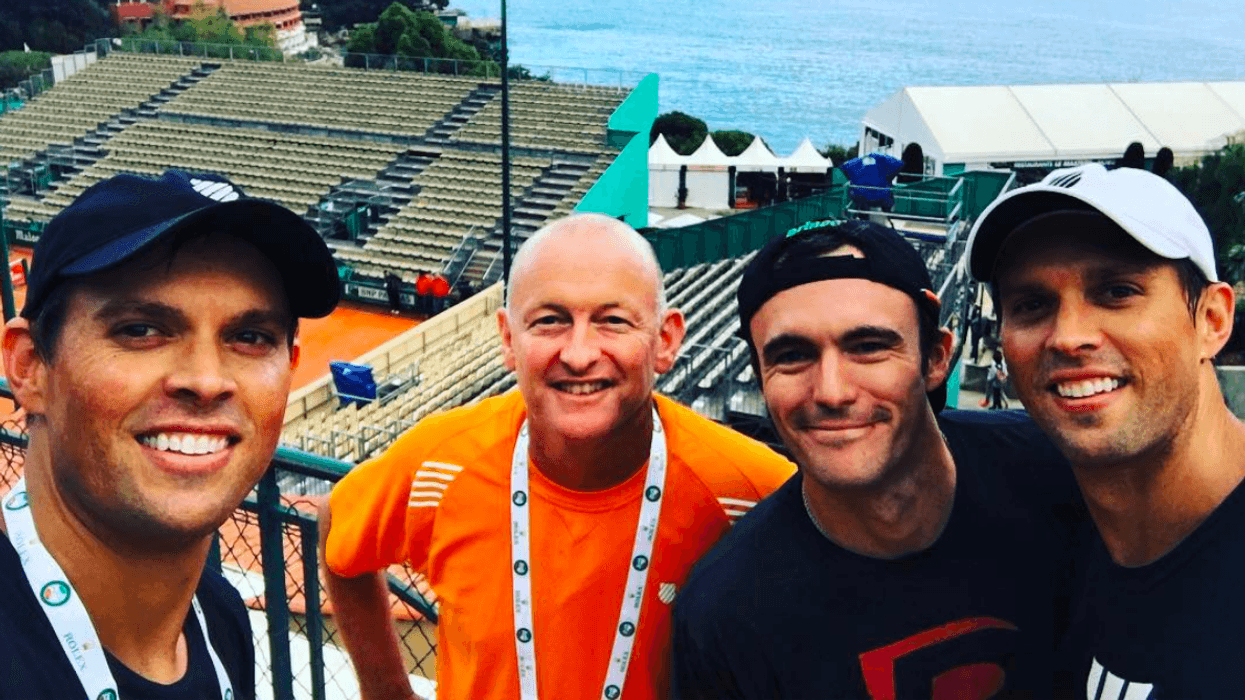

In late 2015, I basically quit playing bass and spent a year traveling with the Bryan Brothers as their fitness coach. For those not familiar with the tennis world, they’re the most successful doubles team of all time, with 119 titles as a team, 16 Grand Slams, an Olympic gold medal, and a record 438 weeks (including 139 consecutive) at number one in the world.

Much like I’m an amateur tennis player, they’re amateur musicians. We met through music, specifically through our mutual friend James Valentine from Maroon 5, who is also way into tennis.

I was going through a divorce and needed a change of scenery. They had just lost early in the US Open and were back in California, so we started training together. They asked if I wanted to come out on tour with them—initially to make a bit of a documentary, as their career was going to wind down in the not-too-distant future. As we trained more, that morphed into going to the world tour finals in London, me becoming part of the team, working the off-season with them at the end of 2015, and then getting on a plane to Australia to start the 2016 season.

“I realized very early on that any serious tennis player on the modern tour doesn’t step foot on a court or into a gym without a coach or trainer. Ever.”

Early in the season, I woke up to my phone melting down in Australia because Bob had given an interview with The New York Times and mentioned me joining the team: “…Janek Gwizdala, an accomplished jazz musician turned fitness guru.” I didn’t realize how many of my music friends were into tennis until that moment, but they sure let me know about it double-quick. Most didn’t believe I was actually on the tour until I was getting them tickets to come see our matches.

All this is to say, I got to see the real day-to-day workings of professional athletes—not just at the top of their field, but at a historically important and legendary point in their careers. We practiced alongside Nadal and Federer regularly, did cryotherapy with Djokovic, and shot the shit in the physio room with Andy Murray. As a tennis fan, it was off the charts.

But when I eventually returned to being a musician and got back into the swing of my musical career, I carried a lot of priceless information with me from my time running around the world on the ATP Tour.

Most importantly, I realized very early on that any serious tennis player on the modern tour doesn’t step foot on a court or into a gym without a coach or trainer. Ever.

And what do we do as musicians? If—and that’s a big if—we go to some sort of music school between 18 and 22, we leave, we’re flat broke because it cost a fortune, and we might never take another lesson for the rest of our careers.

Not once in my 20s, having quit Berklee and moved to New York City, did I have anyone consistently guiding my playing, my mental capacity to deal with what it takes to break into the New York scene, my choices of gigs, sessions, tours—anything. I had friends, sure. We’d talk and commiserate over certain things. But they had no more experience than I did, for the most part.

Sometimes you’d be lucky enough to make friends with a far more senior musician in the scene, and you’d hang on every word and story like a kid getting to stay up late watching TV you shouldn’t see that young. But as amazing as those stories were, they were stories from a bygone era that bore little relevance to where I was at.

What I’ve made a conscious effort to do over the past decade—since that incredible experience of being in a completely different, intense professional scenario—is seek out advice, mentorship, lessons, and coaching whenever possible. Sometimes that’s been for my music, sometimes for business, other times for health or fitness when I’m trying to add something to my routine and want to get the most out of it.

If you’re a beginner or a pro—especially a pro—get a local teacher. Find someone you trust, someone you respect, and take a lesson once in a while. It’s amazing to have someone to talk to, to gain confidence from, and to help you remember you’re not alone in so many of the things we struggle with as musicians.

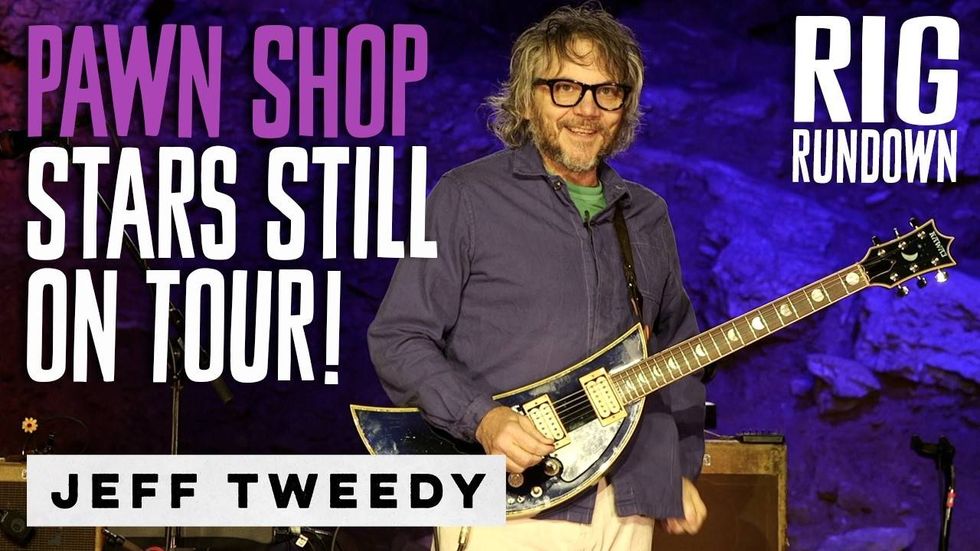

Top 10 Rig Rundowns of 2025

This year was a big one for the Rig Rundown crew! John, Perry & Chris traveled to Boston, Cincinnati, Chicago, Milwaukee, and even a cave in Tennessee, while of course foraging in their home base Music City, to gather the biggest, brightest (and loudest) setups touring the world. Find out the most-popular episodes and behind-the-scenes adventures the tres amigos encountered in 2025.

Rig Rundowns supported by D'Addario

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

Rig Rundown: Jeff Tweedy

The Wilco frontman’s ’90s pawn shop raids are paying off decades later.

Rig Rundown: Marty Stuart & His Fabulous Superlatives

The legendary country musician and his right-hand man, guitarist Kenny Vaughan, prove that Fender guitars through Fender amps can still take you a long way in this world.

THE TOP 10:

10. Marty Friedman Rig Rundown

Marty Friedman and his trusted tech, Alan Sosa, who handles all effects switching manually during the show, showed us the goods.

9. The Who Rig Rundown

The Who need no introduction, so let’s get to the good stuff: PG’s John Bohlinger caught up with the band’s farewell tour at Fenway Park in Boston, where guitarist Pete Townshend’s tech Simon Law and bassist Jon Button’s tech Joel Ashton gave him a look at the gear that the infamous British rockers are trusting for their goodbye gigs celebrating 60-plus years together.

8. Fontaines D.C. Rig Rundown [2025]

The Irish post-punk band’s three guitarists go for Fairlane, Fenders, and a fake on their spring American tour.

7. Steve Stevens Rig Rundown

The Billy Idol guitarist rides his Knaggs into Nashville.

6. Dann Huff Rig Rundown

The all-star producer invites John Bohlinger to his home studio for a glimpse of his most treasured gear.

5. Queens of the Stone Age Rig Rundown with Troy Van Leeuwen

Fresh off a substantial break and a live acoustic recording from Paris’ infamous catacombs, hard-rock titans Queens of the Stone Age stormed back to life this spring with an American tour, including back-to-back nights in Boston at Fenway’s MGM Music Hall.

PG’s Chris Kies snuck onstage before soundcheck to meet with guitarist Troy Van Leeuwen and get an in-depth look at the guitars, amps, and effects he’s using this summer.

4. Keith Urban Rig Rundown for High and Alive Tour 2025

Down Under’s number one country guitar export—and November 2024 Premier Guitar cover model—Keith Urban rolled into Cincinnati’s Riverbend Music Center last month, so John Bohlinger and the Rig Rundown team drove up to meet him. Urban travels with a friendly crew of vintage guitars, so there was much to see and play. In fact, so much that they ran out of time after getting through the axes! Later, Bohli and Co. met up with Urban tech Chris Miller to wrap their heads around the rest of the straightforward pedal-free rig he’s rockin’ this summer.

3. System of a Down's Daron Malakian Rig Rundown

The metal giants return to the stage with a show powered by gold-and-black axes and pure tube power.

Except for two new singles in 2020, alt-metal icons System of a Down haven’t released new music in 20 years. But luckily for their fans, System—vocalist Serj Tankian, guitarist/vocalist Daron Malakian, bassist Shavo Odadjian, and drummer John Dolmayan—took their catalog of era-defining, genre-changing hard-rock haymakers on tour this year across South and North America.

2. Linkin Park Rig Rundown

Linkin Park went on hiatus for seven years after lead vocalist Chester Bennington’s death in 2017, but last September, the band announced that they were returning with new music and a new lineup—including vocalist Emily Armstrong and drummer Colin Brittain. A new album, From Zero, was released in November 2024, followed by the single “Up From the Bottom” earlier this year, and this summer, the band tore off on an international arena and stadium comeback tour. Founding lead guitarist Brad Delson is still a creative member of the band, but has elected to step back from touring. And so on the road, Alex Feder takes his place alongside founding guitarist/vocalist/keyboardist Mike Shinoda, DJ Joe Hahn, and bassist Dave Farrell.

1. Deftones' Stephen Carpenter Rig Rundown

California metal giants Deftones returned this year with Private Music, their first album in five years. In support of it, they ripped across North America on a string of headline shows and support slots with System of a Down.

We linked with Deftones guitarist Stef Carpenter for a Rig Rundown back in 2013, but a lot has changed since then (and as Carpenter reveals in this new interview, he basically disowns that 2013 rig). Back in August, PG’s Chris Kies caught up with Carpenter again ahead of the band’s gig in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where the guitarist gave us an all-access walkthrough of his current road rig.

Acoustic Soundboard: The Ethics and Practice of Revoicing Flat-Top Guitars

Revoicing flat-top steel-string guitars is something I’ve practiced for decades. In the early days, once I discovered what scalloping was and how it affected tone, I began reaching inside instruments and carving braces in hopes of improving their sound. The problem was that I had no real idea what I was doing, no sense of targets, and certainly no clear understanding of purpose. Fortunately, I didn’t attempt this on many guitars, and never on anything of real value.

As time went on and I began building my own instruments, I developed the ability to tune tops through scalloping or tapering braces. This gave me valuable insight into what to look for when approaching revoicing later in my career. The process became more disciplined; it included setting air resonance, balancing top and back frequencies, and measuring deflections.

But the question remains: Should we even be revoicing guitars at all?

In the violin world, revoicing is standard practice. Instruments are designed to be disassembled and worked on, and re-graduating tops is one of the most common procedures performed on vintage violins, violas, and cellos. These repairs are done routinely, even on valuable vintage instruments, and often multiple times across their lifespans. This tradition also extends to historical pitch change, such as the move from A=340 Hz to A=440 Hz, where instruments had to be physically altered to remain functional. Violin makers are trained from the very beginning to understand instrument revoicing and the practice is widely accepted.

“For those with the training and experience, revoicing can transform a lifeless guitar into something inspiring and enjoyable to play.”

Flat-top steel-strings are different. We now have guitars, pre-war Martins in particular, that are considered the Stradivari of the flat-top world. These instruments already sound extraordinary, and carving on their braces would not only be unnecessary, but destructive. Still, not all guitars share this level of excellence even within vintage Martin examples. Over the years I’ve encountered many instruments that simply missed the mark, where the relationships between air, top, and back resonances were poorly balanced.

Take, for example, a Guild D-40 from the 1980s that recently came into my shop. Guilds of that era were well-built, sometimes even overbuilt. This particular guitar measured an air resonance of 101 Hz, a top resonance of 200 Hz, and a back resonance of 207 Hz. The problem was obvious: The top was so tight at 200 Hz it had restricted musicality, and its frequency nearly sat on top of the back, only separated by 7 Hz. Worse, the air resonance, at 101 Hz, was far too high for a large-body guitar, which typically falls around 95 Hz or lower.

This guitar was crying out for a revoice. My plan was simple: reshape and scallop the accessible braces on the top, drop the top resonance into the 170 Hz range, and allow the air resonance to settle near 95 Hz. Step by step, I carved, restrung, measured, and repeated until the targets were met. The top gradually dropped: first to 190 Hz, then 180 Hz, and finally 173 Hz. The air resonance followed, landing at 95 Hz. The results were dramatic. The instrument opened up, resonances began to couple, and its musicality increased significantly.

Of course, there are caveats. Any revoicing work voids a warranty, and on a new instrument that can be a serious consideration. In this case, the Guild was decades old, had changed hands multiple times, and carried no warranty concerns. More importantly, the guitar was so overbuilt that there was little danger in loosening the top.

So, what are the ethics of revoicing? Should you attempt it? The answer is clear: Unless you thoroughly understand resonance, frequency targets, deflection values, and how they interact, you should not. For those with the training and experience, however, revoicing can transform a lifeless guitar into something inspiring and enjoyable to play.

In restoration, the golden rule is to enter and exit an instrument without leaving a trace. But sometimes, as with this Guild, the only way forward is to make meaningful change. Done carefully, with respect for the instrument and for the physics of sound, revoicing is not only ethical; it can be a gift to both the guitar and its player.

Mayones Duvell DT-7 Giveaway!

Win a Maynoes Duvell Dt-7, a 7-string built around clarity, control, and directed tone. Enter by January 30 ,2026.

Mayones Duvell DT 7 String Giveaway

Duvell DT-7

Duvell DT was created with the “Directed Tone” concept in mind. It’s about mastering simplicity and letting the core of the music resonate deeply with both the performer and the audience.

Question of the Month: Is the Vintage Juice Worth the Squeeze?

Question: Is expensive vintage gear really worth the price?

Guest Picker

Iyad Moussa Ben Abderahmane, a.k.a. Sadam (Imarhan)

A: In terms of music gear, I’m not a big collector. But I’ll always pick vintage over newer stuff. I’m a fan of old Gibson guitars—I actually own an SG from the late ’70s, either ’78 or ’79. It sounds amazing and is really easy to play.

Obsession: My current obsession is figuring out how I can help keep the Tamasheq language alive. I’m thinking about writing a book so my kids can learn it, and maybe even finding a way to connect the language to tourism in southern Algeria. I believe we need to develop tourism around Tamanrasset—it could play an important role in safeguarding our culture.

Reader of the Month

Derek Rader

A: My answer … maybe. What motivates you to play and perform is worth the money within a person’s means. If a vintage guitar price isn’t unobtanium, and it has the feel, sound, and mojo, then it’s an emphatic yes! However, a myriad of luthiers and custom shops can provide a similar experience with modern production methods, materials, and electronics, at a lower cost, and the comfort of a warranty. There isn’t a wrong choice if the purchase is motivated by what drives you to play and write music that created the spark to pick up your first guitar.

Obsession: Music theory! A definite area for improvement, and I’m working with the talented Mr. Cris Eaves to improve as a player. Amazing journey!

Contributing Editor

Ted Drozdowski

A: I used to be dismissive about vintage gear until Ronnie Earl let me play his ’64 Strat years ago. I instantly sounded and played better. Now, I treasure my vintage instruments: a ’68 Les Paul, a ’58 Special, a ’72 Super Lead, a ’64 Supro Tremo-Verb, and an original Maestro Fuzz-Tone. Nothing sounds quite like these originals. That said, I can’t imagine spending six digits on a guitar—even if I had that much cake—unless I was also giving a lot to charity.

Obsession: EHX’s new Pico Atomic Cluster Spectral Decomposer. It’s full of sounds I’ve been looking for!

Gear Editor

Charlie Saufley

A: Vintage-or-not is a completely case-by-case thing, and there is no one criteria by which to judge the worth of an old instrument. Depending on your musical needs and manner of expression, some old things that have since been digitized don’t cut it in compact form. For instance, I’m tired of paying to fix my Echoplex EP-3, but I haven’t found a digital alternative that I can physically manipulate in the same way. Three little clustered dials just aren’t going to work or feel like the EP-3’s record-head slider/lever and the perfectly spaced sustain and volume knobs—not to mention the tape irregularities.

Vibes are a real thing too, though. I’m no less psyched when I play something I like on a brand-new Squier. But I also know that engaging with my old guitars and amps is a different kind of fun. It’s just like driving a car from the 1950s or 1960s. The right ones—in addition to feeling as comfortable as old, worn baseball gloves—exude a sense of history and travel and secret stories that appeal to a sentimentalist like myself, and those sensations spark my imagination in ways I can’t put a price on.

Obsession:

Inventing a melody, slowing it down—way down—and fitting a new melody in the spaces in between.

Home Front’s Post-Punk Call to Arms

When he was 10 years old, Graeme McKinnon walked into a pawn shop near his home in Edmonton, Alberta, and bought his first guitar for $50. It was a sharp-angled, all-black axe made by the Japanese company Profile as a low-cost imitation of a Jackson, with a knife-like headstock that jutted curiously upward.

“It looked like a reaper’s scythe,” McKinnon says, recalling the way he’d carry it around town in an awkwardly shaped gig bag. “Everyone thought I had a hunting rifle.”

It was the early ’90s, in the thick of the Seattle grunge movement, and McKinnon’s older cousin would often come over and play him Pearl Jam songs, which he didn’t really like. But when his guitar teacher showed him the Ramones, something unlocked in the youngster. As he improved his chops, McKinnon and his older brother, a bassist, would jam Dead Kennedys and Beastie Boys songs together. McKinnon was hooked on punk rock. “That’s how I cut my teeth,” he says. “The downstrokes from the Ramones stuck with me forever. I always practiced my right hand.”

Fast forward 30 years, and today McKinnon is one half of the post-punk duo Home Front, one of the most hyped-up bands to emerge from Canada in recent years. And the outfit’s new album Watch It Die should earn them a spot on the Mount Rushmore of the current post-punk revival, alongside other breakouts like Fontaines D.C., Idles, and Viagra Boys.

In 2021, McKinnon’s hardcore punk band No Problem was on hiatus and he was looking for a new outlet. That’s when his childhood friend Clint Frazier, previously a member of the electro dance-punk outfit Shout Out Out Out Out, asked him to start a synth-driven band.

“The downstrokes from the Ramones stuck with me forever. I always practiced my right hand.”—Graeme McKinnon

The style that they created combines the jangly sheen of synth-pop, the sneering attitude of old-school punk rock, and the hard-stomping force of oi! and hardcore. The band nicknamed it “bootwave,” a reference to the distinct sound of winter boots marching on ice-crusted snow or the cold concrete of the streets of Edmonton. “Our sound has this duality,” McKinnon says. “There’s the punk side, there’s the synth side, and it’s always these two forces.”

“We’re just trying to find enough space in the songs to do both of them well,” adds Frazier. “I’ve been trying to do that for over 20 years.”

Graeme McKinnon’s Gear

Guitars

Fender Classic Series ’72 Telecaster Deluxe (with new humbucker and graphite saddles)

1979 Gibson Marauder (with P-90 pickup and kill switch)

Hagstrom Viking

Basses

Fender Steve Harris Precision Bass

Fender Bass VI

Guitar Amps

1979 Marshall JMP

Hiwatt Custom 50

Marshall 4x12 cabinet

Bass Amps

Peavey Super Festival Series F-800B

Peavey Roadmaster Vintage Tube Series

Ampeg 6x10 cabinet

Effects

Roland SDE-3000

MXR Carbon Copy

EHX Holy Grail

Van Hall fuzz

MXR Analog Chorus

Various Pro Co RAT models

MXR Blue Box

Strings & Picks

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.010–.046) (Telecaster)

Ernie Ball Power Slinky (.011–.048) (Marauder)

Ernie Ball Regular Slinky (.045–.130), unchanged since 2019 (bass)

Dunlop .73mm picks

Watch It Die follows Home Front’s full-length debut, 2023’s Games of Power. That album earned them positive press from some of the indie-rock scene’s key tastemakers, and it was longlisted for the Polaris Music Prize. The band hit the road hard to support it, embarking on multiple tours of the U.S., the U.K., and mainland Europe, including dates with punk veterans like Dillinger Four and Cock Sparrer, as well as fellow newcomers the Chisel and High Vis.

Like its predecessor, Watch It Die is a record that posits that life is hard, the world is cruel, and it’s easy to feel powerless to make any difference. It’s a headspace that stops just a few yards short of nihilism. But this time around, McKinnon and Frazier are channeling something else, too: hope.

“Our sound has this duality. There’s the punk side, there’s the synth side, and it’s always these two forces.”—McKinnon

“I was using a metaphor of a flower being picked and becoming an ornament in someone’s place, and it’s slowly dying,” McKinnon says. “The secret, the bit that brings a little bit of hope, is that the seed is still in the ground. They can’t see it and they can’t steal it. You watched this part die, but underneath, there’s something else.”

With his previous bands, McKinnon had approached his instrument in much the same way he had since he was a kid: Ramones-style power chords and fast-and-furious downstrokes on his trusty Fender ’72 Telecaster Deluxe. With Home Front, McKinnon had to rethink his playing so that it could coexist with Frazier’s ordnance of analog synths and drum machines.

He looked for inspiration from bands he had always loved but hadn’t previously channeled: England’s ’80s post-punk and new wave exports like New Order, Joy Division, Depeche Mode, the Cure, A Flock of Seagulls, and Blitz. But he wasn’t just looking to do what they did; instead, he wanted to bring his hard-nosed punk style to the mix. “If the electronics are covered, then maybe the play is to bring that punk attack to the guitar to accent the synths,” he says.

On Watch It Die, McKinnon played almost everything through a 1979 Marshall JMP, giving him bright, saturated power chords that tracked well whether he was palm muting or fully strumming. The main exception was a cigar box amp made by a friend who works at an auto shop. It was miked close and cranked, giving them the trashy ’70s punk sound on “Young Offender.”

McKinnon used his Telecaster for most of the record, but he also brought out a 1979 Gibson Marauder with a swapped-in P-90 pickup, which he coupled with a German-made Van Hall fuzz pedal to find the nasty, scooped-out tone that appears on some of the record’s more straight-ahead punk songs like “Young Offender” and “For the Children (F*ck All).” On the new wave jams “Kiss the Sky” and “Between the Waves,” he pulled out a Hagstrom Viking that engineer Nik Kozub recorded by miking the semi-hollow body itself, giving the songs a thin, percussive jangle without having the low end of a proper acoustic muddying the mix.

For McKinnon, it was important to get his palm mutes sounding clean and punchy, and to have them perfectly aligned with the synth arpeggiators—even when he’d add swirls of reverb and delay in his chain. Enter his secret weapon: an old Roland SDE-3000 digital delay that he got from the TV studio where he works. McKinnon and Frazier used its BPM-sync function to dial it in to precisely match the tempo of the drum machines.

McKinnon also records all of the bass lines for Home Front. That, of course, comes with its own military-grade arsenal. On “Empire,” he pulled out all the stops. For the grand finale, he chained the Van Hall into a fully cranked Pro Co RAT, into the MXR Blue Box octave fuzz, and finally into a dimed-out Peavey Super Festival F-800B. It was “the nastiest fuzz bass I’ve ever played,” he says, creating a wall of sound inspired by My Bloody Valentine. Frazier accentuated that enormous gain-fest with eighth-note Roland 808s that he painstakingly tuned, note by note, so that each kick would follow the bass line, creating a pulsating effect that makes rhythmic sense of McKinnon’s fuzzed-out chaos.

That is, fittingly enough, the thematic throughline of Watch It Die: making sense of the madness. “Our lives are chaos all the time,” says McKinnon. “We have jobs that are going to end at any moment. The rent is too high, the groceries are too expensive, all these stresses, and then every time you open up your phone, there’s atrocities in the world. There’s shit your government’s doing, police breaking families apart, this is stuff you’re constantly thinking about, and it’s always hitting you.”

But Home Front aren’t just going to wallow in their sorrows. “On this record, I didn’t want to sound like, ‘Shit’s bad. I’m just gonna be kicking rocks,’” McKinnon continues. “It’s more like, ‘Shit’s bad, but this is how we’re gonna work through this, by having outlets that allow us to form like Voltron to terrorize the oppressors.’” PG

Source Audio Encounter Review

Reverb and delay. What two effects are better suited to live side-by-side in one pedal? Source Audio’s new Encounter reverb and delay is a mirror image of the company’s Collider, which explores the reverb/delay combo via a vintage lens. The mirror by which Encounter reflects the Collider, however, is more like the funhouse variety. There are many psychedelic, cosmic, and wildly refracted echoes to utilize in the Encounter. There are lots of practical ones that can be tuned to subtle ends, too. But Encounter’s realm-of-the-extra-real extras make it a companion for players that ply dreamy musical seas. It’s incredibly fun, a great spark for creativity, and, most certainly, a place to lose oneself.

Exponentially Unfolding

Of Encounter’s six reverb modes and six delay modes, four of them—the hypersphere, shimmers, and trem verb reverbs, and the kaleidoscope delay—are entirely new. Hypersphere, fundamentally, makes reverberations more particulate. Source Audio says it’s a reverb without direct reflections. In their most naked state, these reverberations can still sound a touch angular and perhaps not quite as ghostly and fluid as “no direct reflections” suggests. But they are still complex, appealing, immersive sounds. Odd reverberation clusters can conjure a confused sense of space and highlight different overtones and frequency peaks in random ways. At settings where you can hear this level of detail, hypersphere shines, particularly in spacious solo phrases. Hypersphere also features phase rate and pitch modulation depth functions via the control 1 and control 2 knobs, and they can further accent and enhance those frequency peaks, creating intoxicating, deep fractal reflection systems.

“Blends of the delay and reverb are the kind of places where you can lose track of a rainy day.”

The new trem verb mode can be practical or insane. The two effects together are a pillar of vintage electric guitar atmospherics. But the Encounter’s trem verb explodes those templates. As with the hypersphere mode, trem verb can zest simple chord melodies by using extreme effect settings at low mixes, where chaotic, half-hidden patterns dip in and out of the shadows, sometimes creating eerie counterpoint. But I loved trem verb most at extremes—mostly high mix, feedback, and decay settings with really slow modulation. Sounds here can be intense and vague—like strobe flashes piercing drifting fog. It might not be an ideal place to indulge fast, technical fretwork, but it’s a wonderland for exploring overtones, drone, and melodic possibilities.

Incidentally, the trem verb is a great match for the six delays, and the new kaleidoscope delay in particular, which fractures and scatters repeats in a million possible directions and spaces. Blends of the delay and reverb are the kind of places where you can lose track of a rainy day. The sound permutations often seem endless, and finding magic can take some attention and patience. But you can strike gold fast, too. You have to take care to save settings you really love (you can store as many as eight presets on board, and 128 total via midi) because it’s hard to resist the urge to meander through— and meditate on—hours of sound without stopping. Not all of the Encounter’s sounds are perfectly pleasing. Some combinations reveal peaky little chirps that betray digital origins—the merits of which are subjective and contextual. For the most part, though, the combined sounds are liquid and vividly complex, and can be especially enveloping at high mix and feedback.

Extended Reach

If the onboard controls don’t get you in enough trouble, downloading the Neuro 3 app, which unlocks deep control and functionality, is a minor wormhole. Take the case of trem verb—you can use Neuro 3 to change the wave shape or set up the reverb to affect the wet signal only, just the dry signal, or both of them. All of these changes open up a new system of tone caves as the sound evolves. If you’re deep in the nuance of a mix or arrangement, this functionality can be invaluable. And it’s a boon if you have nothing but time on your hands. In a state of engaged, intuitive workflow, I like to avoid these kinds of app dives. But having that much extended power on your phone or computer is impressive.

Neuro 3 extends the capability of the Encounter in other ways, too. The SoundCheck tool within Encounter is home to prerecorded loops of various instruments that you can then route through a virtual Encounter pedal. That means you can explore Encounter’s potential while stuck in a train station. It’s a real asset if you want to understand the pedal as completely as possible, and certainly a way to extract the most value from the unit’s considerable $399 price.The Verdict

About that price. It looks steep. For most of us, it’s a significant investment. But when I consider how many sounds I found in the Encounter, how compact it is, and the possibilities that it opens up in performance and portable production (especially when you factor in the stereo ins and outs), that investment seems pretty sound. I must qualify all this by saying I was happiest with the Encounter when exploring its spaciest places—the kind of atmospheric layer where Spacemen 3, ambient producers, 1969 Pink Floyd, and slow-soul balladeers all hang. But there is room to roam for precision pickers that background radical effects, too.

Still looking to justify the cash outlay? Consider the Encounter as a portable outboard post-production and mixing asset. If you’re creating music built on big, shape-shifting ambience, it’s a cool thing to have in your bag of tricks. Different artists will mine more from the Encounter than others, so you should consider our ratings scores on a sliding scale. But as you contemplate the Encounter, be sure to factor in mystery paths that will beckon when you dive in. There’s lots of fuel for creation along most of them.

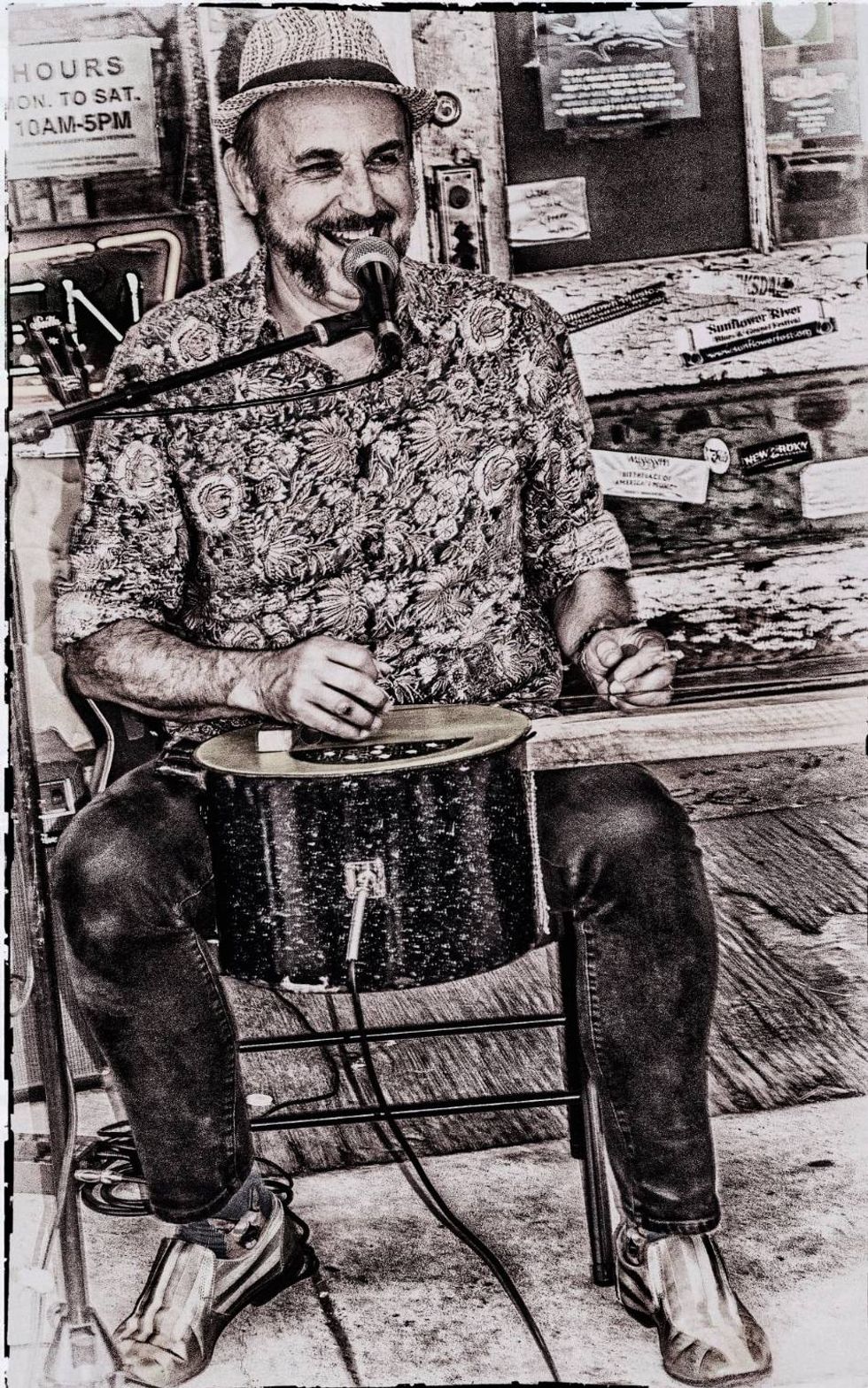

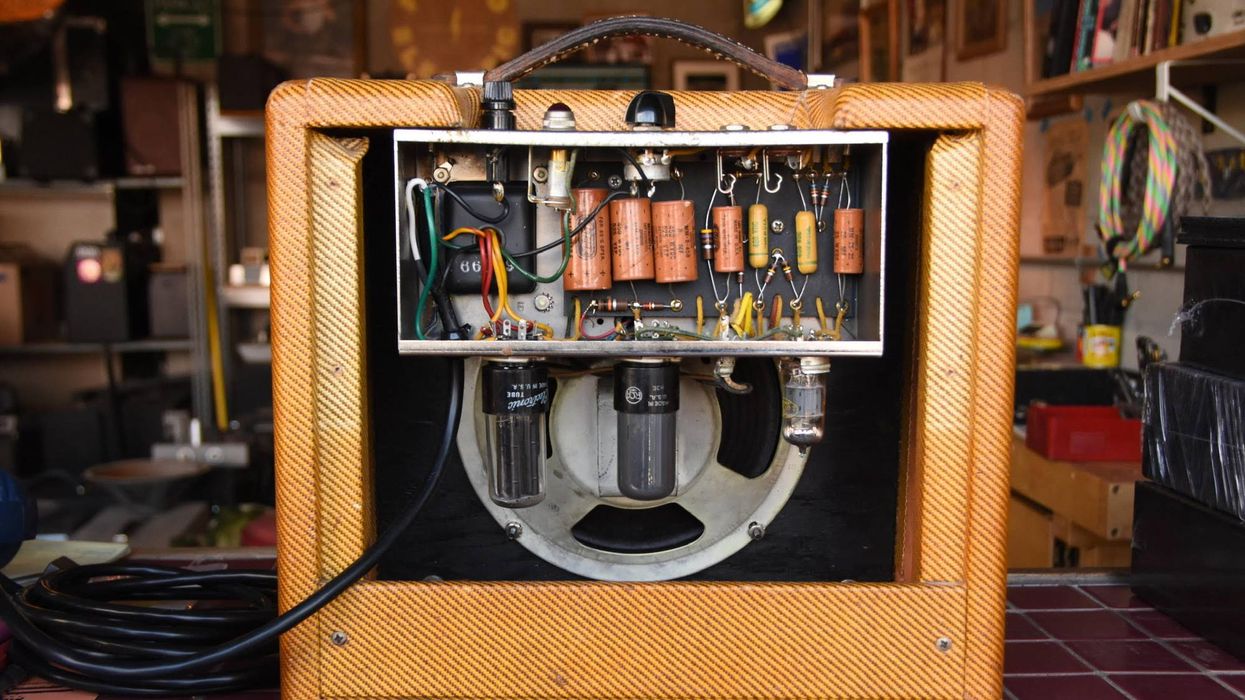

On the Bench: 1959 Fender 5F1 Champ

There is an element of time travel in opening up an amp to find original circuitry from decades prior. As an amp repair technician, there are few things better than finding that circuit untouched. And that feeling is enhanced when the amp has sentimental value.

In this case, I received a 1959 Fender 5F1 Champ that belonged to my client’s grandfather, who used it along with his Fender Champion lap steel guitar. He was a Polish immigrant who worked in the coal mines of Pennsylvania and enjoyed teaching himself a range of subjects from mathematics to music.

The 5F1 “narrow-panel” Champ was produced from 1956-1964. All of the tweed-era amps were special, but the 5F1 is a quintessential amp of that period. It’s a simple circuit, with only one volume control. This is as pure as it gets, allowing the unfiltered guitar signal to really breathe through the speaker and into our ears.

When you think about early rock ’n’ roll, and that warm and crunchy guitar tone, you’re hearing a tweed Champ. Eric Clapton, Joe Walsh, and Keith Richards were all known to use a 5F1 in the studio. At low volumes, a guitar sounds smooth and rich. As the amp’s volume gets cranked, it starts to growl, filling the room with pure grit.

“It was customary for the amp’s builder to sign their name on this piece of tape, and in many cases during this time, the builder was a woman.”

At first glance, I was impressed with the overall condition of the amp. The tweed and grill cloth are in beautiful shape, with barely any flaws. Opening up the amp only entails the removal of 4 screws. I held my breath as I placed the asbestos-lined panel—which was meant to act as a heat shield—outside. I then sealed it with a clear lacquer, to avoid disturbing the material.

Immediately, my eye was drawn to the tiny piece of masking tape that had been placed inside the chassis. It was customary for the amp’s builder to sign their name on this piece of tape, and in many cases during this time, the builder was a woman. Sometimes that piece of tape is missing or illegible, but I was happy to see the name “Lily” clearly visible in this amp.

This Champ still has its original speaker, an 8" Oxford, which is dated the 3rd week of 1959. Sadly, but not surprisingly, the speaker did need a re-cone. Over time, it’s common for the paper cone to crack or tear, which was visually obvious in this case. If we were to put a signal through the speaker as it was, it would sound horribly blown.

The circuit itself is pristine, sporting all of the original components that had kept the amp alive for the last 66 years. The orange Astron filter and cathode bypass capacitors caught my attention as soon as I saw them.The filter capacitors are an important part of the amp, as they smooth or “filter” noise out of the power supply. Eventually, these capacitors dry out and can cause loud humming or other issues. The cathode resistor sets the bias for each cathode-biased tube, which, in the 5F1, includes the output tube. The cathode bypass capacitor works in parallel with this resistor to resurrect the gain and tonal color that tends to flatten out through this process. When these capacitors start to drift from factory specification, they can cause strange tone or signal issues.